The post below generated a lively response and I thought the thread was both interesting and important enough to continue it as a new post.

One reader responded:

Why do judges reviewing judicial misconduct usually not name the judge subject to investigation? See, e.g., In re Judicial Misconduct. Many respondents in the ABA survey said that judges are unaccountable. When reviewing courts a) hold judicial misconduct proceedings in private and b) refuse to even identify the subjects of colorable complaints, what should the public think?

The question is a good one. I actually support more "sunshine" on the judicial disciplinary process. I think far to much of the process takes place in secret and while the motive is that airing dirty judicial laundry in public erodes confidence in the judicial system, I think the secrecy has a similar effect.

I know that there are some places with a history of corruption in the judiciary and that would clearly justify a low opinion of judges for that reason alone but I think the results of the ABA survey have more to do with the perception that judges ignore the will of the majority, are "making up law" instead of just applying it and are unaccountable for doing so.

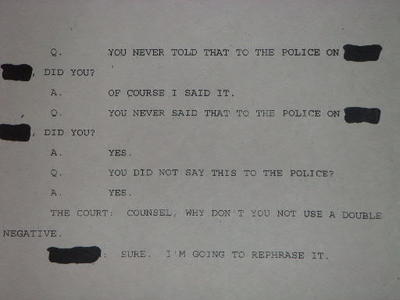

I know that the vast majority of complaints against judges come from non-lawyers and are based upon dissatisfaction with the outcome of a particular case and those are usually dismissed summarily since complaints that an error of law was made, even if well founded, is not grounds for disciplinary action anywhere I know of. Outside of systems where judges have life tenure, judges can simply not be re-appointed or re-elected if they demonstrate sufficient incompetence in applying the law correctly. When judges really get in trouble, it usually has to do with their demeanor on the bench. They may consistently display an attitude or engage in conduct that suggests partiality or bias.

I personally don't have a problem with secrecy as to the filing of complaints determined to be unfounded but once a judicial regulatory body finds that there is sufficient evidence to proceed against a judge on ethical grounds, I agree that the process and proceedings should be open.

I think the reasoning used by some that proceedings against federal judges should be secret because federal judges can only be removed through impeachment proceedings, is a bit circular since Congress is a political body and would be more inclined to institute such proceedings if the public outcry were great enough - which it may well be if the public knew what the judge had done.

The simple notion that you have to face a periodic review of your performance keeps most non-federal judges pretty sensitive to how they are perceived by the litigants and the public.

I think the fundamental perception problem which unfortunately is all to often aided and abetted by some judges, is that the judiciary is occasionally perceived as a group of "philosopher kings" who, with the purest of motives, think of themselves as wiser than the people and their elected representatives.

Sometimes criticism of a judge is well taken and sometimes it is not. We can all agree that cases should be decided by the consistent application of legal principles and not by popular opinion and we can further note that judges do not control the way cases are presented to them and in an adversary system, the relative competence and professionalism of the advocates will often be a determining factor in the outcome of a case. However, it is also a fact that we are an outcome oriented society and that means that quite often the judge (silently) takes the heat for a result that nobody likes but which was compelled by the law and the record in the case.

Typical of this mindset and as an aside which also makes the point, one regular reader of this blog has characterized me variously as "a right wing slogan-shouter" who relies on organizations with an agenda to "tell me what the law is" and who would never "rule in favor of unpopular causes." Beyond noting that this site is more "blog" than "blawg" and I that post links from

any source with a story that I, and perhaps you, might find interesting, bizarre or amusing, I would also point out that as a judge I rule on "cases" not "causes." From his knee-jerk posts, I would also hazard a guess that this particular reader has never read any of the rather large number of opinions I have authored over the years. I leave to others any evaluation of my performance as a judge. While I don't take myself very seriously (as evidenced by this blog), I do take my job very seriously indeed.

The bottom line for me is that taking heat for your decisions goes with the oath and the robe and I should be able to truthfully say that I kept an open mind and gave both parties to the case fair consideration of their legal arguments and the record presented and to justify every judicial decision I make by pointing to a constitutional provision, statute or ethical canon and if I can't, shame on me, and if it gets to the point when I have to defend my actions, the public, who pay my salary, have a right to examine and debate those decisions and my justification for them. I don't have lifetime tenure and I am periodically called upon to defend the way I approach my job and I think that is the way it should be.

Addendum - As I was publishing this post, the preceding one received this comment which is worth reproducing here in its entirety:

"Indeed, perhaps judges should stop pretending that they possess some ability to discern the ultimate meaning of the constitution and will call close cases in favor of the government."I don't want to hijack the judge's comment thread, but it would be interesting if judges would say the following:

1. As a matter of separation of powers, I will call the close ones in favor of the government or;

2. Because I believe that courts are the final arbiters of the Constitution, and because it is the duty of the courts to protect minority rights, I will call the close ones in favor of the individual.

In truth, judges generally adopt one of these models. Because the models are equally valid, I don't consider opinions issued under either, activist. Perhaps if judges overtly admitted this, there would be less confusion and thus (hopefully) less to complain about."

My response is that I don't usually have the luxury of following any model because precedent, whether I like it or not, will usually guide the outcome but in those relatively few cases of constitutional first impression that do come along, I don't follow either model. I think the basic historical premise of all constitutions is that they represent a compact between the people and their government and are intended to protect people from overreaching by their government.

In construing a constituional provision, I try to discern meaning from the words used in a constitution the same way you do with a statute. What is the plain meaning? What was the policy intent of the framers at the time? How have similar words used in other parts of the Constitution been construed? I, for one, try very hard not to substitute my personal views for policy decisions that belong, in the first instance, to elected representatives of the people.

What do you think?

Not surprisingly, Court TV's CEO likes the idea of televising arguments in the Supreme Court of the United States.

Not surprisingly, Court TV's CEO likes the idea of televising arguments in the Supreme Court of the United States.