The

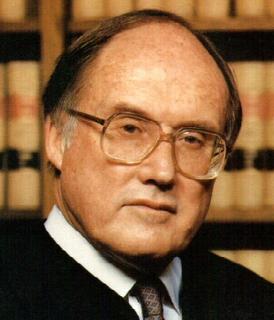

New York Times obituary of Chief Justice William Rehnquist paints a picture of a brilliant, witty, even quirky jurist who left an indelible mark on American jurisprudence.

He was also a very nice man.

I met him quite by accident some years ago when my wife and I took our then ten year-old son to Washington D.C. for a little "civics lesson" which involved taking him to the various Smithsonian museums, the White House, Capitol, etc., including the Supreme Court.

After the usual tour, we were headed downstairs to the cafeteria for lunch when I noticed Chief Justice Rehnquist shuffling down the hallway from the Press Office to the elevator. He was in obvious pain (he had severe back problems most of his adult life). He slowly threaded his way through about 40 tourists, none of whom recognized him. When he got to where we were standing, I introduced myself and my family. He spent most of the next 10 minutes talking to my son about the Court and its history. My son was enthralled by the story and impressed that the top judge in the country would take a few minutes to speak to a child about the place he worked.

He was often portrayed as imperious in the media but you will never convince my son (or me).

Rest in peace. Your duty is done.

The ABA Journal reports here that "[m]ore than half of Americans are angry and disappointed with the nation'’s judiciary."

The ABA Journal reports here that "[m]ore than half of Americans are angry and disappointed with the nation'’s judiciary."