When I see a link at a great blog like

Arbitrary and Capricious with a title like "

Field Guide to the Hard-assed Judge," you just know that I'm going to check it out.

The link led to

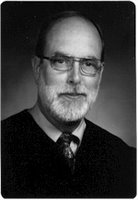

this post that seems to suggest that "hard-assed" appellate judges look like the one in the picture to the right. The post notes that the "physiognomy of a hard-assed judge" is basically a robe above which is perched a face with a high forehead and beard.

What I found most telling was that the proximate cause of the "hard-assed" characterization for the appellate judges in question, was a prosecutor who was apparently playing fast and loose with the record and was caught at it by the judges. I guess I am more than a little surprised that the author of the post seems to think that judges getting upset about a lawyer lying to them was much ado about nothing.

I don't know about other judges, but in similar circumstances, I would also be more than a little upset. It is bad enough when any lawyer is caught lying to a court. Aside from the fact that it is unethical to deliberately mislead a tribunal, your credibility as an advocate, both in that case and any future case before any of those judges, is toast.

I suppose that some lawyers think that appellate judges aren't likely to be very familiar with the trial record and perhaps in some courts that may even be the case. On the other hand, the culture on my court and, I suspect on most other appellate courts, is to be very familiar with all portions of the record that relate to the issue(s) on appeal. In my court, you are very likely to get caught if you pull a stunt like this.

It is even worse if, as here, the prevaricating lawyer is a prosecutor. The law holds prosecutors to a higher standard than other lawyers (even on appeal). During a long former career as a prosecutor I prided myself on that fact and I have no problem insisting that prosecutors meet that higher standard when they are in my court.

If in the collective judgment of the three-judge panel a prosecutor was deliberately misrepresenting the record, we would not "have him clapped in irons" but the majority of my colleagues and I would likely have admonished him in open court for violating the ethical rules, terminated his oral argument immediately and written a letter to the disciplinary arm of the bar signed by all three judges, complaining about the ethical breech and enclosing a transcript of the argument or brief and the appropriate pages of the record.

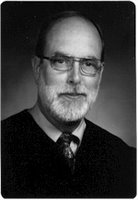

By the way, just to set the record straight, I look nothing like the picture above. We "hard-assed judges" look more like this:

As you may have noticed, I have been blogging at a much reduced rate of late. This is mostly due to a sudden increase in work. I have been reading many more briefs and transcripts than usual and I took a bunch of these home to review over the weekend and buried in one of the transcripts I found this little gem:

As you may have noticed, I have been blogging at a much reduced rate of late. This is mostly due to a sudden increase in work. I have been reading many more briefs and transcripts than usual and I took a bunch of these home to review over the weekend and buried in one of the transcripts I found this little gem: