Over at LawCulture,

Over at LawCulture, In pertinent part, Prof. Brooks writes:

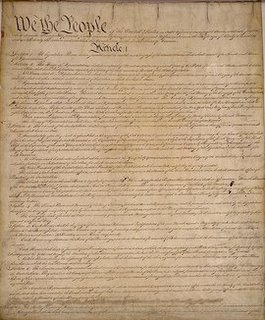

Inevitably, as time goes by after the initial drafting and adoption of a constitution, it becomes increasingly likely that changing circumstances will make some/many of the constitution's provisions less salient and helpful. If the Constitution is difficult to amend, as is the U.S. Constitution, this problem may worsen with time. There are ways around the problem-- one can develop interpretations and doctrines that allow us to "bring the Constitution up to date" without actually amending it-- and this is of course what we have done in the U.S. I think this is as it should be. But the problem is that the more one is forced to depart from a "straight" reading of the Constitution to justify "modern" solutions to problems-- the more one is forced to rely on legal fictions and creative interpretive extensions of the text-- the more one risks undermining other values associated with the rule of law, like transparency.I must be missing something but I thought by definition laws are written to provide both notice and consistency in a code of conduct. Neither of these is found in evolving individual concepts of how others should conduct themselves. I suppose I am oversimplifying things but if a written constitution is a contract or compact between the people and their government (or in the case of the United States, a three-party compact between the federal government, the states and the people), it seems to me that the "rule of law" requires that the contract be adhered to and if it is so "out of date" that it does not provide a "modern solution," it should be renegotiated by the parties through amendment, no matter how "unwieldy" that process may be.

Here's the paradox: if a society "strictly" adheres to a constitution as the decades and even centuries go by, it's doing itself a disservice, since the constitution will become more and more "out of date," but if a society relies on ever fancier interpretive footwork to shoehorn modern understandings into constitutional categories, perhaps the society risks undermining public commitment to the rule of law itself, since the "ordinary" person (and even many lawyers) will have less and less faith in the process of constitutional interpretation (or in judges, presumably).

The alternative to that approach is the "philosopher king" (and queen) approach recently advocated by Canada's Chief Justice and apparently by Prof. Brooks. To call this approach "following the rule of law" seems to me to be absurd on its face and in any event, I submit that this "rule by the whim of unelected elitists" approach has proven at least as "unwieldy" as Prof. Brooks suggests those pesky written constitutions are.

*** As "Anonymous" points out in the comments, Professor Brooks teachs at UVA, not Yale (although Yale is where she got her law degree) - sorry about that.

2 comments:

The argument also seems to ignore the fact that the constitution provides for its amendment; a difficult process, no doubt, but one precisely gauged to address the problem of obsolesence.

I suspect that what the author fears is not a written constitution, but rather, judges who will strictly construe such a constitution, which then leaves important social changes in the hands of the people (who will have to democratically amend the constitution by persuading their fellow citizens)rather than the courts.

Rosa Brooks teaches at the University of Virginia Law School, not at Yale. And yes, I think you did miss her point.

Post a Comment